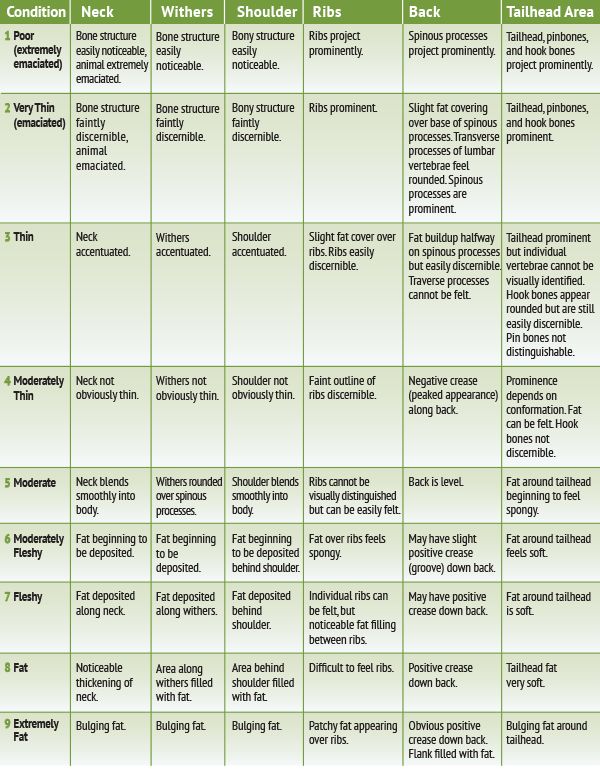

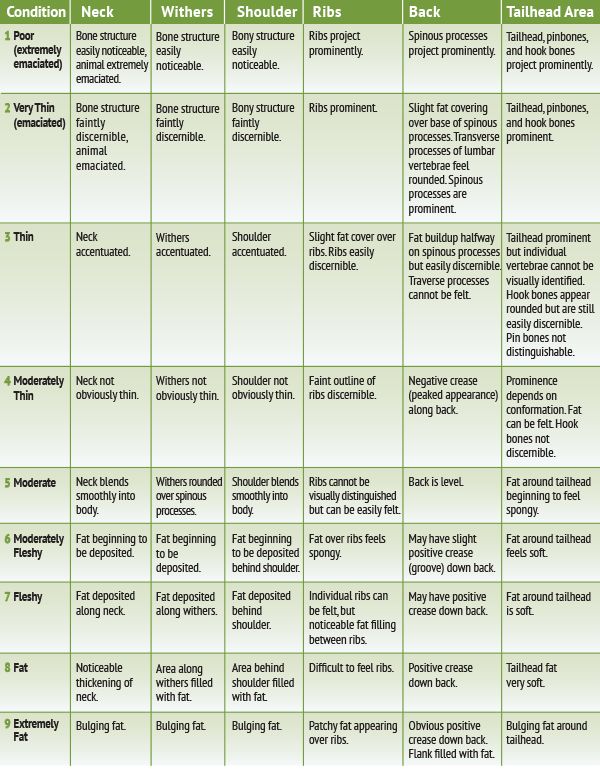

Henneke Body Condition Scoring Chart

The prognosis for the malnourished horse varies with the severity of the body weight loss and the length of time the horse has been subjected to insufficient nutrient intake. Starved horses quickly run out of body fat reserves to mobilize, and then they begin to use muscle mass for energy. This can include skeletal muscle as well as protein from the breakdown of essential organs such as the heart, liver, and kidneys. When starvation goes on for too long, the damage to muscles and body organs can become catastrophic. Horses that are allowed to lose weight sufficient to drop them down to a body condition score of two or less on the Henneke scale of 9 are far less likely to ever return to health.

In addition to acute body condition loss, starvation in the horse causes a multitude of symptoms including weakness, heart arrhythmia, and electrolyte irregularities. Starvation will exacerbate existing conditions such as arthritis or joint issues, and will reduce immune function.

Horses that are thin but also plagued with parasites, such as ticks or lice, will have a more difficult time regaining health once on a suitable feeding regime. Horses that are senior or suffering from debilitating health conditions, such as lameness or poor teeth, can be even more difficult to refeed to health.

Bringing a Malnourished Horse Back to Health

The most effective way to refeed a malnourished horse is to first establish a plan that includes your veterinarian. Horses that have been subjected to prolonged nutrient deprivations could have potential physical damage to body tissues and your veterinarian will need to assess the animal before a refeeding program is initiated.

An assessment of current body weight and desired body weight is necessary, as is an estimation of current body condition. A weight scale for this kind of workup is the best, but a weight tape can also be used. Equine weight tapes are available at most stores that supply equine feed. When weight taping an emaciated horse, don’t be surprised if the tape suggests that the horse is heavier than expected. Weight tapes are best used for horses that are in “average” body condition and are not always accurate for the emaciated horse. Despite that, the use of one as part of your initial plan can be helpful in giving you a “baseline” weight measurement to use going forward. Pictures taken at the initiation of the refeeding program and at regular intervals during the course of treatment can be invaluable when assessing the progress of the horse.